Over the past few years I’ve grown to like PHPStan, a static analysis for PHP projects. It’s a great tool for catching bugs and improving code quality. In this post, I’ll show you how to use PHPStan for WordPress plugin or theme development.

What PHPStan does

There are many tools for analyzing PHP code tools out there, such as PHP-Parallel-Lint for syntax checks, or PHP_CodeSniffer to check conformance with coding standards. The latter is often used in WordPress projects (including core itself!) thanks to the dedicated WordPress Coding Standards ruleset.

In addition to these tools, PHPStan tries to find bugs based on the information it derives from typehints and PHPDoc annotations, without actually running your code or writing any tests. Among the things it tests are the existence and accessibility of classes, methods, and functions, argument mismatches, and of course type mismatches.

Strongly-typed code gives PHPStan more information to work with. Keep in mind that typehinted and annotated code helps both static analysis tools and people understand the code.

Getting started

While I try to cover the basics of how to set up PHPStan, I recommend reading the project’s excellent Getting Started guide, which goes more into detail.

To get the ball rolling, install PHPStan via Composer:

composer require --dev phpstan/phpstanCode language: Bash (bash)After that you could already try running it like this:

vendor/bin/phpstan analyse srcHere, src is the folder containing all your plugin’s files.

I usually prefer setting such commands as Composer scripts so I don’t have to remember them in detail. Plus, the src path can be omitted if it’s defined in a configuration file. But more on that later.

My typical Composer script looks like this:

{

"scripts": {

"phpstan": "phpstan analyse --memory-limit=2048M"

}

}Code language: JSON / JSON with Comments (json)Note how I also increase the memory limit. I’ve found this to be necessary for most projects as PHPStan tends to consume quite a lot of memory for larger code bases.

Work around PHP version requirement

PHPStan requires PHP >= 7.2 to run, but your actual code does not have to use PHP 7.x. So if your project’s minimum supported PHP version is lower than 7.2, I suggest a small workaround: install PHPStan in a separate directory with its own composer.json file, like build-cs/composer.json.

This file is separate from your project’s Composer configuration and contains only the dependencies with a higher version requirement:

{

"require-dev": {

"phpstan/phpstan": "^1.10"

}

}Code language: JSON / JSON with Comments (json)After that, add a script to your main composer.json file to run PHPStan from the newly created directory:

{

"scripts": {

"phpstan": [

"composer --working-dir=build-cs install",

"build-cs/vendor/bin/phpstan analyse --memory-limit=2048M"

]

}

}Code language: JSON / JSON with Comments (json)This way, running composer run phpstan will analyze your code as usual, even if the main configuration requires an older PHP version.

Note: It goes without saying that I highly recommend reconsidering your project’s version requirements. Then you won’t have to add such workarounds.

Telling PHPStan about WordPress

Remember how PHPStan analyzes your code to check the existence of classes and functions? It looks for them in all your analyzed files as well as your Composer dependencies. But WordPress core isn’t really a dependency of your WordPress plugin.

So without any additional configuration PHPStan will first not know about WordPress-specific code like WP_DEBUG and WP_Block. You have to first make it aware of them.

Thankfully, the php-stubs/wordpress-stubs package provides stub declarations for WordPress core functions, classes and interfaces. They’re like source code, but only the PHPDocs are read from it. However, we are not going to use them directly.

Instead, you should install the WordPress extension for PHPStan. Not only does it load the php-stubs/wordpress-stubs package, it also defines some core constants, handles special functions like is_wp_error() or get_posts(), and apply_filters() usage.

Simply require the extension in your project and you are all set:

composer require --dev szepeviktor/phpstan-wordpress phpstan/extension-installerCode language: JavaScript (javascript)No further configuration is needed, phpstan/extension-installer handles discovery automatically.

Stubs for other WordPress projects

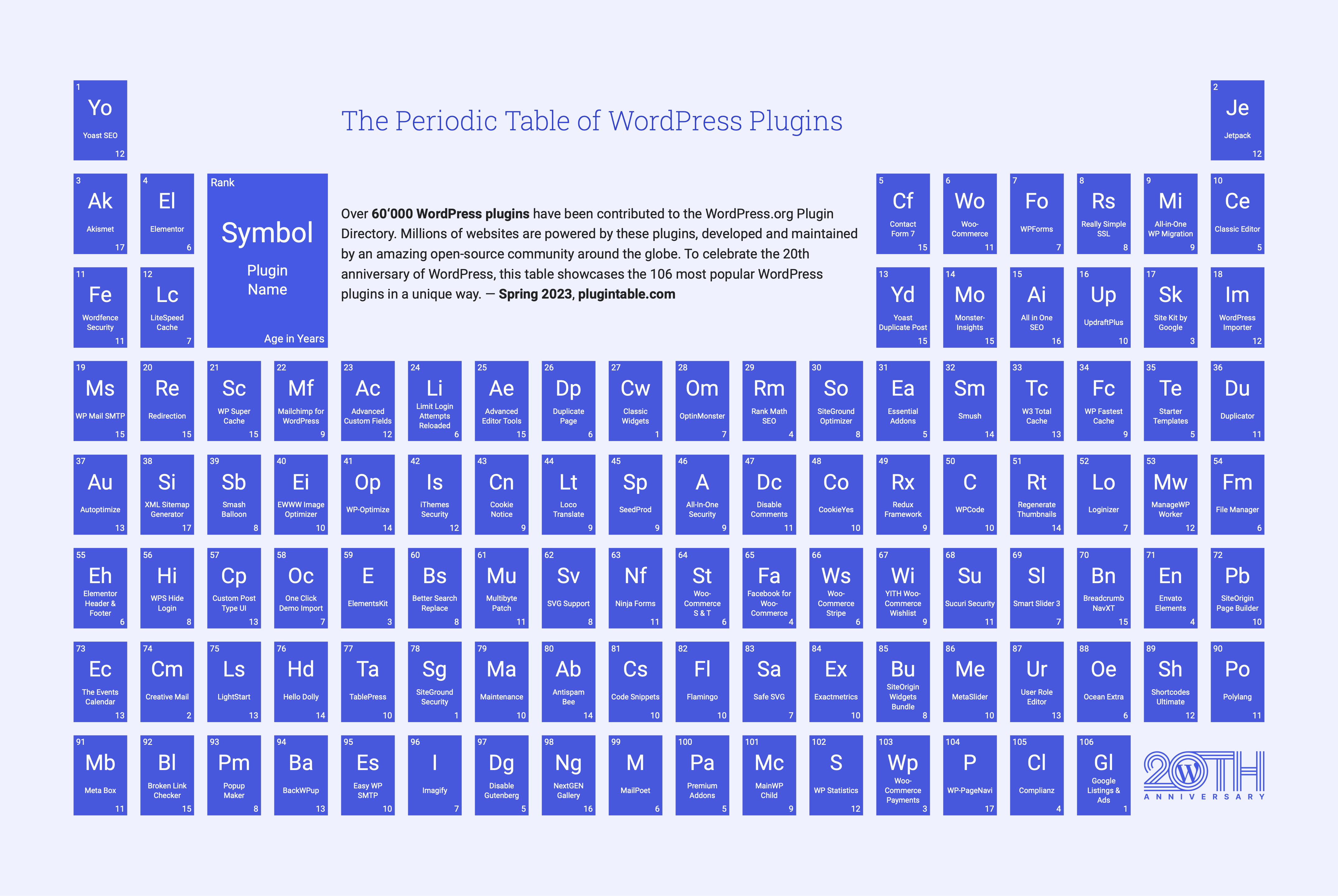

If your WordPress plugin or theme integrates with other plugins like for example WooCommerce, you will also need to provide stub declarations for them to PHPStan.

Luckily, the PHP stubs library already provides stubs for WooCommerce, Yoast SEO, ACF Pro and even WP-CLI.

You can also generate stubs for other projects yourself using the available generator library.

Baseline configuration

Now that we have installed all the necessary tools, we can start with our initial configuration.

Here it’s important to know about the different rule levels PHPStan supports. The default level is 0 and is for the most basic checks. With each level, more checks are added. Level 9 is the strictest.

If you want to use PHPStan but your codebase isn’t quite there yet, you can start with a lower level and increment it over time.

Alternatively, you can use PHPStan’s baseline feature to ignore currently reported errors in subsequent runs, focusing only on new and changed code. This way you can check newer code at a higher level, giving you time to fix the existing code later.

Let’s say we want to start with level 1 and analyze everything in our src folder as mentioned above. Our minimum configuration file will look like this:

parameters:

level: 1

paths:

- src/Code language: YAML (yaml)Save this file as phpstan.neon.dist. PHPStan uses a configuration format called NEON which is similar to YAML, hence the file name.

This configuration file is also where you point PHPStan to all the different stub declarations if you have any.

Now you can truly run composer run phpstan and PHPStan will analyze your project while being fully aware about the WordPress context.

Some errors you might see after your initial run are “If condition is always true” or “Call to an undefined function xyz()”. Some of them are pretty easy to resolve, others require consulting the documentation or the help community.

Improving PHPDocs

PHPStan relies on typehints and PHPDoc comments to understand your code. PHPDocs can also provide additional information, such as what’s in an array.

When there are errors being reported in your existing code base, chances are that the PHPDoc annotations can be improved.

Learn more about PHPDocs basics and all the types PHPStan understands. It also supports some proprietary @phpstan- prefixed tags that are worth checking out.

Sometimes you might get errors because of incorrect PHPDocs in one of your dependencies, like WordPress core. In this case, I suggest temporarily ignore the error in PHPStan and submit a ticket and pull request to improve the documentation upstream.

Usage in REST API code

A special case for some WordPress projects when it comes to PHPDoc is the WordPress REST API. If you have ever extended it in any way, for example by adding new fields to the schema, you’ll know how the fields available in a WP_REST_Request or WP_REST_Response object are based on that schema (plus some special fields for the former, like context or _embed).

Let’s say you have some code like this in your REST API controller:

$per_page = ! empty( $request['per_page'] ) ? $request['per_page'] : 100;Code language: PHP (php)A static analysis tool like PHPStan cannot know that per_page is a valid request param defined in your schema. $request['per_page'] could be anything and thus $per_page will be treated as having a mixed type.

You could solve this with an inline @var tag:

/**

* @var int $per_page

*/

$per_page = ! empty( $request['per_page'] ) ? $request['per_page'] : 100;Code language: PHP (php)However, this should only be used as a last resort as it quickly leads to a lot of repetition and the annotations can easily become outdated.

Luckily, the WordPress stubs package provides a more correct way to describe this code, using array shapes:

/**

* @param WP_REST_Request $request Full details about the request.

* @return WP_REST_Response|WP_Error Response object on success, WP_Error object on failure.

*

* @phpstan-param WP_REST_Request<array{post?: int, orderby?: string}> $request

*/

public function create_item( $request ) {

// This is an int.

$parent_post = ! empty( $request['post'] ) ? $request['post'] : null;

// This is a string.

$orderby = ! empty( $request['orderby'] ) ? $request['orderby'] : 'date';

}Code language: PHP (php)Using PHPStan for tests

So far I have focused on using PHPStan for analyzing your plugin’s main codebase. But why stop there? Static analysis is also tremendously helpful for finding issues with your tests and assertions therein.

To set this up, you will need to install the PHPStan PHPUnit extension and rules, as well as the WordPress core test suite stubs so PHPStan knows about all the classes and functions coming from there, like all the factory methods.

composer require --dev phpstan/phpstan-phpunit php-stubs/wordpress-tests-stubsCode language: JavaScript (javascript)Note: this assumes you are already using phpstan/extension-installer.

To add the new stubs, amend the configuration file like so:

parameters:

level: 1

paths:

- src/

scanFiles:

- vendor/php-stubs/wordpress-tests-stubs/wordpress-tests-stubs.phpCode language: YAML (yaml)With this, you are all set.

Again, I find running PHPStan on tests very useful. It helps write better assertions, find flawed tests, and uncover room for improvement in your main codebase.

Running PHPStan on GitHub Actions

Once you have set up everything locally, configuring the static analysis to run on a Continuous Integration (CI) service like GitHub Actions becomes a breeze. You don’t need to configure a custom action or anything. Simply setting up PHP and installing Composer dependencies is enough. Here’s an example workflow:

name: Run PHPStan

on:

push:

branches:

- main

pull_request:

jobs:

phpstan:

name: Static Analysis

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Setup PHP

uses: shivammathur/setup-php@v2

with:

php-version: 'latest'

coverage: none

tools: composer, cs2pr

- name: Install PHP dependencies

uses: ramsey/composer-install@v2

with:

composer-options: '--prefer-dist --no-scripts'

- name: PHPStan

run: composer phpstanCode language: YAML (yaml)Recommended PHPStan Extensions

So far I have introduced the WordPress and PHPUnit extensions for PHPStan, but there are many more that can be valuable additions to your setup. Remember: with phpstan/extension-installer they will be available to PHPStan automatically, but some of them can be further tweaked via the configuration file.

swissspidy/phpstan-no-private

Detects usage of WordPress functions and classes that are marked as@access privateand should not be used outside of core. And yes, I actually wrote this one.phpstan/phpstan-deprecation-rules

Similar to the above, this extension detects usage of functions and classes that are marked as@deprecatedand should no longer be used. Again very useful in a WordPress context.phpstan/phpstan-strict-rules

The highest level in PHPStan is already quite strict, but if you want even more strictness and type safety, this is the extension you want. It’s also possible to enable only some rules.johnbillion/wp-compat

Helps verify that your PHP code is compatible with a given version of WordPress. It will warn you for things like using functions from newer versions without an accompanyingfunction_exists()check.

Wrapping Up

I hope this post serves as a good introduction to using PHPStan in a WordPress project. There are so many more things I could cover, like how to set the PHP version, the PHPStan Pro offering, or the interactive playground. But I didn’t want to make this even more overwhelming, so maybe I’ll save these tips for another post.

If you have any questions about PHPStan or want to share your experiences with it, I would love to hear them in the comments!

Finally, if you end up using PHPStan in your WordPress project, consider donating to either PHPStan itself, or Viktor Szépe who maintains the WordPress extension and stubs.